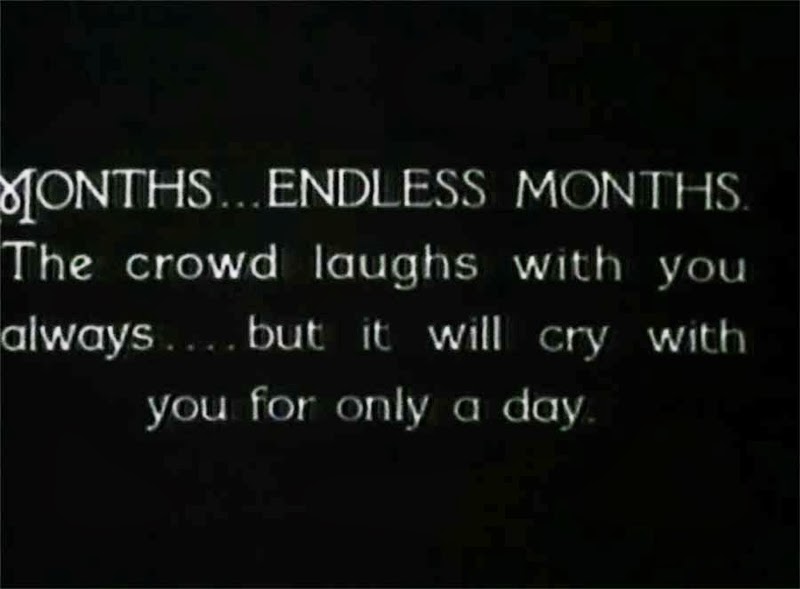

The clip above is from a so-called soundie, made in 1943 to promote The Mills Brothers’ hit “Paper Doll.” The woman in the lap of the Mills Brother on the far left, best visible at about the one-minute mark, is Juanita Moore. She was 29 years old, and this was the first piece of film that ever captured her. She died on New Year’s Day, age 99.

With the exception of the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times, Moore’s obituaries have been a bit light on biographical material, focusing on her Best Supporting Actress nomination for Douglas Sirk's 1959

Imitation of Life. It's the story of two single mothers, Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) and Annie Johnson (Moore) and their daughters. Lora becomes a successful actress as her daughter Susie (Sandra Dee) becomes increasingly lonely. Annie's light-skinned daughter Sarah Jane is determined to "pass" for white; Sarah Jane is played by

Susan Kohner, who is now the only one of the film’s central quartet still living. The AP, which has

offended in the past,

added another to the files with the words chosen to describe this women's picture, widely considered a landmark in the treatment of race on the American screen. “Weeper” — “tearjerker” — the Siren will believe that these descriptions are not evidence of condescending sexism when they are commonly applied to something like

Spartacus or

The Shawshank Redemption, and not until.

So with facts gleaned primarily from Sam Staggs’

Born to Be Hurt: The Untold Story of Imitation of Life, the Siren would like to fill you in on some of Moore’s life outside her one Oscar-nominated triumph. Anyone who reveres Moore, or this film,

needs Staggs' book, which is a monument to loving, obsessive completism. It encompasses everything, from costumer Jean Louis to a detailed view of John Stahl’s 1934 version of Fannie Hurst’s novel, even an interview with the anonymous ghostwriter of Lana Turner’s autobiography. Staggs apparently knew Moore well, and she told him a lot about her background, her friends, her times.

Moore was born in Mississippi, the youngest in a family of seven girls and one boy. Her parents moved when she was a toddler to South Central Los Angeles, where they were able to make a good middle-class living from, among other things, running a laundry. At age 15 Moore came down with polio, and she said later that the doctors of the time were not much interested in treating a black girl. Her mother and sisters massaged her legs with olive oil, and she slowly recovered.

She could sing, and she could dance, and at least one teacher planted the idea that Juanita could grow into an entertainer. She attended performances by the Lafayette Players, a pioneering black theatre ensemble, thrilling to shows such as

Madame X and

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It was foreshadowing; throughout her life, with one exception, Moore got stronger, bigger roles with African American theater groups than she ever did in Hollywood.

Moore’s parents were religious, and afraid of the lowdown influences of a life in the theater. She ditched a short stint at college and made her way to Harlem, where she wouldn’t have to worry that Mr. and Mrs. Moore were worrying. Soon Moore was in the chorus line at Small’s Paradise, a “black and tan” Harlem club, meaning that while the audience was mostly white, blacks attended and mingled freely.

Moore married dancer Ananias “Nyas” Berry of the Berry brothers, an act that was one of the few rivals to Harold and Fayard Nicholas in terms of grace and acrobatics. (

Here they perform“You’ll Never Know” in

Lady Be Good;

here they introduce Eleanor Powell in

Fascinating Rhythm; Nyas

is profiled here, and his own story is quite a saga.)

Ella Fitzgerald became a friend, and Moore had run-ins with Ethel Waters. Juanita Moore was notably polite about almost anyone she ever worked with, but Waters she invariably described as “the bitch of all time” — a phrase she once used, Staggs says, in front of a preacher, who spent the rest of the evening snickering about it.

Moore danced at the Zanzibar, atop the Winter Garden on Broadway. The Berry Brothers performed at the West 48th St. location of the segregated Cotton Club. At first the owners would not let Moore sit in the audience and watch her husband dance. Eventually they consented to let her sit at a remote table, by herself. In

Imitation of Life, Juanita Moore’s Annie trawls nightclubs in search of her daughter Sarah Jane. In every place, Annie is seated in Siberia, lest she contaminate the white patrons' tables. As Staggs notes, Moore needed no advice on how to play the way that felt.

As the craze for nightclub entertainment waned, Moore went back to Los Angeles and began to get parts in movies. Small parts. Maid parts. She had a relatively substantial part in

Affair in Trinidad, and spoke kindly about Glenn Ford and how hard he worked to make her feel comfortable in that Rita Hayworth vehicle. Director Vincent Sherman, in his autobiography, reminisced about “Juanita Hall” — another black actress, most famous for playing

Bloody Mary in

South Pacific.

Moore was cast in

Band of Angels as a slave owner’s mistress; while Yvonne De Carlo played a plantation owner's daughter who’s sold into slavery after his death, because her mother was a black slave. Despite Raoul Walsh at the helm it’s a tedious picture. Moore had to sashay into one scene wearing a Creole getup, and Walsh told her to whisper bawdy stories in De Carlo’s ear. The result was one moment in the film that doesn't feel strained or silly.

Meanwhile, Moore also became involved with the Ebony Showcase Theatre. It was founded by actor Nick Stewart, who took his profits from playing Lightnin’ on the

Amos ‘n Andy radio show, and used them to build his dream of a dedicated, artistic black acting troupe. For the Ebony, Moore played Ines in Sartre’s

No Exit, and other roles over the years. Later she became a founding member of the Cambridge Players.

Her marriage to Berry had ended with his death from cancer in 1951. One day Moore was crossing the street, and a bus nearly hit her. The bus driver poked his head out to yell, “You better watch your step, young lady!,” and Moore yelled back at him, “You crazy-ass bus driver, what are you trying to do, kill me?”

They were married the next year, had a son, and stayed together until Charles Burris died in 2001.

Moore took a job as a waitress at a chicken restaurant to make ends meet. One of her regulars was Marlon Brando; he accompanied her to classes at the Actors Laboratory Theatre, where after an all-night shift she once fell asleep and snored so loudly than Elia Kazan yelled “What the hell is that?” Kazan already knew her, from the part she had played in 1949’s

Pinky, a story where yet another white actress — Jeanne Crain — played a tragic mulatto. It was something of a motif in Juanita Moore’s career, white actresses playing mixed-race parts, and Moore making a bit role memorable, this time as a nurse.

If you want to hear Juanita Moore sing, watch the clip above, from

Women’s Prison in 1955, in which she sounds wonderful while she’s down on her knees, scrubbing the prison floor.

If you want to see Juanita Moore dance, watch Frank Tashlin’s 1956

The Girl Can’t Help It,

here, bookmarked just past the 53-minute mark, when she, Tom Ewell and Jayne Mansfield are watching Eddie Cochran on TV. Moore starts dancing, and it’s delightful, and over way too soon, because the film was about Ewell and Mansfield. Moore was playing the maid.

The Siren well remembers Moore’s bit in

Something of Value, a 1957 film about the Mau-Mau uprising in Kenya, where Moore plays a woman who’s beaten until she admits helping the rebels. She was not, on this occasion, anybody’s maid.

Moore was about 45 when

Imitation of Life was released (her birth date is a bit fuzzy) and given Hollywood’s unforgiving attitude about women who dare to get older, the film was unlikely to bring her over-the-title stardom in any case. But for a white actor, a performance such as that would surely have brought steady, substantive character work. It worked that way for Thelma Ritter, 45 years old, after one scene in

Miracle on 34th Street. It didn’t happen for Moore. Her movie roles after her Oscar nomination were mostly minor, although they did include what’s reportedly a good turn in

The Singing Nun (the Siren has never made it through that one). In the theater, she played

A Raisin in the Sun in London, and Sister Boxer in James Baldwin’s

The Amen Corner on Broadway in 1965. In 1970, Moore played an Annie-esque part in the Mexican production

Angelitos Negritos, based on a film that may or may not have been a direct spin on the original 1934

Imitation of Life (it's complicated). She spoke the lines in Spanish as much as possible, even though she knew she'd be dubbed.

In the 1970s she made movies like Jules Dassin’s

Uptight, and

The Mack with Richard Pryor. Still later, a generation that had grown up with Sirk’s movie on TV cast Moore in other roles in films and on TV. She told Staggs of how, on the first day of shooting

Paternity, Burt Reynolds took her around the set pointedly introducing her as “

Miss Moore. Miss Juanita Moore.” In other words, this is a legend, mind your manners. Moore was deeply touched.

Black folks - like other folks who have felt ignored, underrepresented or stereotyped - have always rooted for the blacks we could find in celluloid. I remember how a showing on TV in the mid-'60s of that 1959 melodrama Imitation of Life ripped like a tornado through our emotions in Conyers, Ga. I couldn't have been older than 12. This melodrama, starring Lana Turner to some but Juanita Moore to us, was about a saintly black woman who worked herself to death for a daughter who chose to pass for white.

-E.R. Shipp, Daily News, 2002

When Richard Pryor was in the army in Germany, according to a 1999 New Yorker profile, he went to a screening of

Imitation of Life, and a white soldier laughed loudly at the Annie and Sarah Jane scenes. Pryor and some other black soldiers beat him up. The incident landed Pryor in jail.

It is that kind of movie. Once seen under the right circumstances, it inspires a devotion that will brook no argument. We may disagree about certain elements, about whether the term “camp” applies to elements of the “blonde” storyline, for example. Staggs says yes; the Siren says no, and has written before about the importance of

Lana Turner and

Sandra Dee’s work. But no fan of this film has any reservations about Moore.

When the Siren first saw

Imitation of Life, sometime in her early teens, she was swept away by the unutterable sadness of Annie Johnson, who begins as Lora Meredith’s compatriot in single motherdom, and ends as Lora’s maid. A beloved and respected maid, but a maid nonetheless. All the while Annie adores and tries to protect Sarah Jane, who yearns to escape what she sees as a prison of blackness, and is willing to deny her mother repeatedly to do it. When Sarah Jane is still a little girl played by Karin Dicker, she is caught for the first time passing for white at school. When they return to the apartment, the little girl storms off saying no one is her friend. Lora says, “Don’t worry Annie. I’m sure you’ll be able to explain things to her.” Annie responds, “I don’t know. How do you explain to your child, she was born to be hurt?”

Down the years you develop a relationship with a film you love, and so it has been with the Siren. That line of Moore’s is a killer even on first viewing. But the last time she saw the movie, the Siren was also struck by Moore’s delivery, as she stares after her daughter and seems to speak almost without thinking. There’s an undertone of resignation, a sense that Annie knows she’s telling the truth to someone who does not and can not understand what she means.

![]()

Moore’s performance has layers upon layers, right from the great opening, when Sarah Jane and Lora’s daughter Susie are playing on the beach, Lora mistakes Sarah Jane for Annie’s charge, and Annie corrects her: “Yes, ma'am. It surprises most people. Sarah Jane favors her daddy. He was practically white. He left before she was born.” Again, watch Moore’s face as she says that. Annie’s deeply religious, but in the sly light in her eyes is the idea that Sarah Jane’s father was a handsome man, that this was a torrid relationship and Annie remembers that pleasure even now that he’s left her. This is a vibrant, fully sexual woman, though we never see anyone in the picture treat her that way. The closest anyone comes is when Sandra Dee’s Susie asks Annie about “boys. What do you think about kissing, Annie?” Annie responds with “Well, there’s kissing, and there’s kissing,” and again we see the remembrance of love move across her features.

There are many instances where Sirk’s camera, and Moore’s performance, clue us in to the fact that Annie has large parts of her existence that are out of camera range, and thus well away from the white characters and us, the audience. She tries to convince Sarah Jane to go to a church social, telling her that there are plenty of nice boys there, and Sarah Jane snaps back, “Busboys, cooks, chaffeurs.” Annie's hurt tells you that her daughter is rejecting the place that her life revolves around; a black church, full of people she loves, where Annie is herself in a way that she isn’t in the Meredith house.

The final proof of that comes in Annie’s deathbed scene. A heartbroken Lora says to the woman who’s shared her life, “It never occurred to me that you had friends.” And Annie responds, without a trace of rancor, “You never asked.” In that single line reside generations of “the help” who kept their most important selves apart from their employers.

Douglas Sirk’s

Imitation of Life, and his other great movies, tell us that when people are forced, against their character and inclination, into prefab roles that society has made for them, the result is agony. Juanita Moore’s career was shaped by forces that had nothing to do with her talent. She had a personality that struck people as nothing much like Annie’s. Staggs says Moore was “a real live wire,” with flashes of anger as well as salty humor. Moore told Staggs she had based Annie on one of her sisters, a devout woman who was the embodiment of Christian goodness.

Yet Annie, despite her suffering, is not passive; warmth and kindness are active choices, all the more so when made under harsh circumstances. Juanita Moore, who left behind friends, family, and millions of admirers, had more of Annie in her than she acknowledged.