(This is a disgracefully belated entry for the Film History Blogathon. The Siren's post, on 1928, would have been part of the 1927-1938 section, hosted by Ruth at Silver Screenings. For the years 1915-1926, your hostess is Fritzi at Movies, Silently; and 1939-1950 can be found at Aurora's place, Once Upon a Screen. Please click through to those host blogs to find a plethora of wonderful, and prompt, blog entries on many aspects of film history.)

Death is a good career move, goes an old movie joke that the Siren has never found funny. It was never less true than it was for silent film, which died after a brief illness. Probably it was younger than Marilyn Monroe, although like many another cinema great, the birth date’s hard to pin down.

Some early deaths do enshrine a legend; some even elevate a talent that might have burned out. Silent film died and stayed buried. If you were still around, and your name wasn’t Charlie Chaplin, you didn’t get much time to mourn. Pull up your socks and deal, that was the only way to survive. Who knows how many faceless names in the credits were walking around, not with mike fright, but mike shock.

As is common when talking about a life cut off in its prime, the Siren starts with the wake. King Vidor, in his 1953 autobiography A Tree Is a Tree, paints a scene that’s both gallows-funny and tragic.

We had no movieola in the first days of sound, and during the editing of Hallelujah [1929] I saw a cutter literally go beserk at his inability to get the job done properly. The walls of his cutting room were lined with multitudes of shiny film cans containing the mass of sound and picture tracks. Returning from a projection room after many hours of labor he discovered that the scene was still out of synchronization and let fly with a reel against the solid wall of cans. This precipitated an avalanche of thousands of feet of loose film that engulfed the two of us. The hysterical cutter fell on the floor sobbing helplessly. I unwound him from the tangled maze and drove him home to the care of his wife. He remained in bed a week before he could again undertake the task of editing the film.

Vidor was a spiritual, contemplative person infrequently given to flashes of temperament. But he was also worn out and, probably, worried to death. “I felt that by this mechanical advance the movies were losing a beautiful impressionistic quality that would be hard to replace in the technique of the new medium,” he wrote about the necessity of adding dialogue to a craps-game scene in Hallelujah. “In the light of experience,” he adds hastily, “I have since changed my mind, but the forced transition saddened me for quite some time.”

Who can blame him. One year before, even as sound invaded, the silents were still at their peak. That’s a fact endlessly repeated, and yet it’s one of those things that always gives the Siren a jolt, like Orson Welles’ age when he made Citizen Kane, or Gone With the Wind’s inflation-adjusted gross. Look at the silents that opened in 1928. Contemplate their technical bravado, their thematic originality, their vivid acting: Street Angel. The Cameraman. The Circus. The Italian Straw Hat. Laugh, Clown, Laugh. Underground. The Passion of Joan of Arc. The Wind...

One of those 1928 films, The Crowd, is not only the Siren’s favorite silent, but one of her favorite films, period. A Tree Is a Tree goes into this film’s conception, the casting, the camerawork. Vidor quotes the rave reviews with poignant pride. The Crowd tells the story of John Sims, who’s raised to believe great things await him, and then they never arrive. John moves to Manhattan (where else for a striver?) but he never strikes it rich, never climbs the ladder at work or anywhere else. He meets a nice girl, they marry and have a family. Their joys become fewer and the hardships harder, until a blow lands that many couldn’t recover from. John’s one act of heroism is simply deciding to carry on, a moment that only the small boy who shares it with him will ever truly appreciate.

“Daring” means a number of different things these days. Sometimes it’s used as a synonym for “impenetrable,” but in American film it’s often something to do with taste. Is it cynical, is it dark, will it make Grandma stomp out of the theater to ask the manager if his mother knows he’s showing this filth.

The Crowd is its own kind of daring, due mostly to King Vidor, but in some measure also to Irving Thalberg. Some people say Thalberg was only and always a middlebrow purveyor of quality Oscar-bait. Vidor — who can’t be said to have idealized his producer — would not have agreed.

His movie The Big Parade was still packing cinemas, and the director found himself buttonholed by Thalberg and asked what his next project would be.

I really hadn’t an idea ready, but one came to me in the emergency. “Well, I suppose the average fellow walks through life and see quite a lot of drama taking place around him. Objectively life is like a battle, isn’t it?” While I groped, Thalberg was smiling.

“Why didn’t you mention this before?” he asked.

“Never thought of it before,” I confessed.

“Have you got a title.”

“Perhaps One of the Mob.”

Thalberg showed immediate enthusiasm. “That a wonderful title, One of the Mob. How long will it take you to write it?”

“Two or three days.”

“If you need any help, let me know.”

“Thanks,” I said, and we parted.

Now this is the way I believe a film should begin.

“MGM,” Thalberg once told Vidor about an idea that wasn't The Crowd, “can certainly afford a few experimental projects,” although as Erich von Stroheim would have pointed out, Thalberg’s indulgence of artists did have its limits. Accordingly Thalberg soon rejected the title One of the Mob as too suggestive of a proletarian tract, and The Crowd emerged. Vidor and Thalberg wanted a “documentary flavor” and an unknown actor as John seemed the ideal way to get it. The search was fruitless until one day a man brushed by Vidor, a man with a face that looked familiar not because the director had seen it before, but because it was a face you could never pick out of a crowd, or a mob, or (in this case) a lot full of extras. Vidor gave the man his card and told him to call for a chance at a part. The man never called, and Vidor couldn’t remember the name. Finally the director went to the rosters of extras and lit on the words that wouldn’t stick in his brain: James Murray. The extra hadn’t called Vidor because he thought the director wasn’t serious about the job.

Vidor cast Eleanor Boardman, his wife at the time, as Mary Sims, and put her in plain clothes and minimal makeup that diminished her considerable beauty. Murray turned out to be a difficult person, fated to meet a bad end due to alcoholism and sheer cussedness. The cinematographer was Henry Sharp, who also did Duck Soup, It’s a Gift and was active through the 1930s; but this was his peak.

Fired up by what he called “directors of vision” from Europe — he names Murnau, du Pont, Lang and Lubitsch — Vidor set about creating his own. He describes the movie’s most famous shot, where the camera scales a vast office building, sweeps through a window and swoops over hundreds of desks until at last it discovers John Sims, bored out of his mind.

A scene was made in New York City at the entrance of the Equitable Life Insurance building at lunch hour. The camera started its upward swing and when the screen was filled with nothing but windows, we managed an imperceptible dissolve to a scale model in the studio. The miniature was placed flat on the floor with the camera rolling horizontally over it. In the selected window was placed an enlargement of a single frame of the previously photographed interior view. As the camera moved close to the window another smooth dissolve was made to the interior scene of the immense office. The desks occupied a complete, bare stage and the illusion was accomplished by using the stage walls and floor, without constructing a special set. To move the camera down to Murray, an overhead wire trolley was rigged with a moving camera platform slung beneath it. The counterbalanced camera crane or boom had not yet been designed and built, but the results we achieved were identical with those of today.

So breathtaking is this scene that 13 years later, when Orson Welles and Gregg Toland moved a camera up a building, seemingly through a skylight, and down to Dorothy Comingore drunk at a table in a deserted club, the effect was still thrilling. It was thrilling almost 20 years after that, when Billy Wilder’s camera in The Apartment crawled up another tower to find Jack Lemmon at his desk at Consolidated Life of New York. Wilder never hesitated to credit Vidor.

Vidor, in 1953, still loved to talk about the technique behind The Crowd.

In a scene where the nervous husband paces the floor of the hospital corridor during the delivery of his first child, we wanted to give the impression that many husbands were also going through the same suspense and agony. We wanted a tremendously long hospital corridor stretching, as it seemed, to infinity. Cedric Gibbons, head of the art department at MGM, designed and constructed a corridor in forced perspective, with each receding door becoming smaller and smaller. We even considered putting midget husbands outside these miniature doors, finally decided to keep the mob of anxious husbands in the foreground of the shot.

“Midget husbands.” That’s ridiculous, but it’s also symbolic, isn’t it, of how fired up these artists were about getting every part of the movie right.

For scenes of the sidewalks of New York, we designed a pushcart perambulator carrying what appeared to be inoffensive packing boxes. Inside the hollowed-out boxes there was room for one small sized cameraman and one silent camera. We pushed this contraption from the Bowery to Times Square and no one ever detected our subterfuge.

This was precisely the kind of shot that would suddenly become problematic a short time later. The obstacles of shooting with sound were swiftly dealt with, but imagine going from a camera in a glorified baby carriage, to a camera enclosed in a soundproof booth.

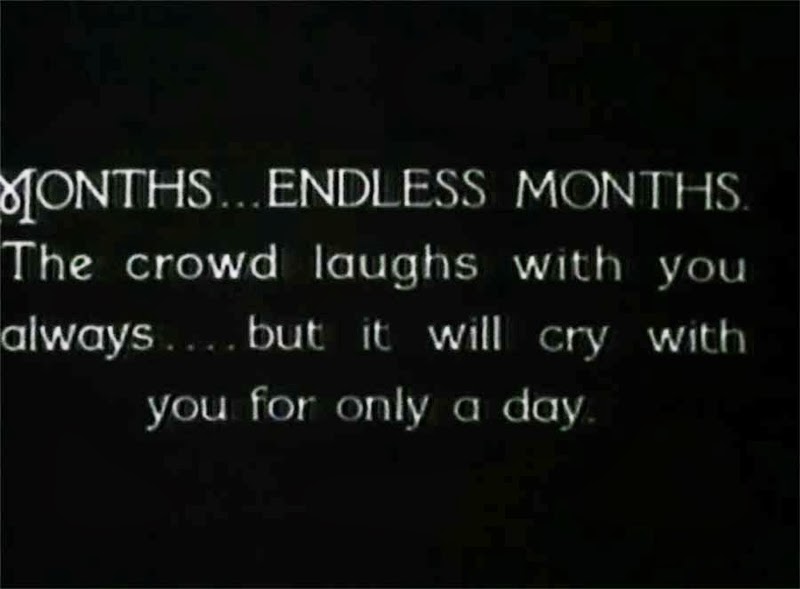

John and Mary take a first date to Coney Island, that Cote d’Azur for the working stiff, happily mingling with the teeming, entertain-me masses. (Whatever happened to that spinning-plate thing, where people sit, link arms and try not to get hurled off? The world lost a great metaphor when that ride went away.) Later, when his daughter is critically injured, John stumbles out of his apartment building and into the street, pleading with the masses not to make so much noise. As the people keep streaming past him, John is admonished by a cop, in an intertitle of perfect callousness and truth: “Get inside! The world can’t stop because your baby is sick!”

But much of the film takes place in their small apartment, through the frustrations of daily life. John plays his ukelele and dreams up slogans; it is evident early on that he’s a dreamer, not an achiever. He buys his wife an umbrella (an umbrella!) as a token of affection, then can’t seem to keep himself from yelling at her when she opens it in the house. Everything in the apartment breaks, and there’s a squabble to go with each mishap. Boardman’s best moment is when she’s staring at the door after her heedless, cranky husband has slammed out, and she remembers (with zero intertitles) that she had, somehow, forgotten to tell him she’s pregnant.

And there’s the end, the unforgettable end, where John goes with his family to see a clown in a theater, and as Vidor says, “the camera moved back and up to lose him in the crowd as it had found him. In the course of the narrative he had not made a million dollars, nor committed a heinous crime, but he had managed to find joy in the face of adversity.”

King Vidor made two other films in 1928, The Patsy and the dazzling Show People, both with Marion Davies. Once Show People was done he decided that since he’d made three films set in France (The Big Parade, Bardelys the Magnificent and La Boheme) it was time to see the country in real life. He and Eleanor Boardman met F. Scott Fitzgerald on the boat going over, and in Paris they all hung out at Fitzgerald’s apartment, watching Zelda demonstrate the steps she was learning in ballet class. Vidor met James Joyce, who refused to make eye contact in order to conceal his failing vision, and Ernest Hemingway, as that writer strode out of a bookstore with his baby son tucked under one arm.

Then, abruptly, it was time to come home.

One day as I sat alone near the Place de L’Opera, a copy of Variety arrested my attention. Emblazoned across the front page in bold type was the headline: PIX INDUSTRY GOES 100% FOR SOUND. I had been away for only two months, but during that brief period a major transition had taken place in the motion-picture industry...I knew I could no longer sit complacently at sidewalk cafes. The dragon of sound must be met head-on, and conquered.

Vidor went on to make many more good movies, some of them great. Memoirs are tricky as memories are tricky. The Siren believes the anecdote she started with, the one about trying to synchronize the sound for Hallelujah. And she has zero factual backup for what’s she about to say, so take this as the fantasy it almost certainly is. But every time she reads that story, the Siren wonders if perhaps — just perhaps — the nameless cutter was a polite fiction, and the man who threw that reel against a wall of film was King Vidor himself.